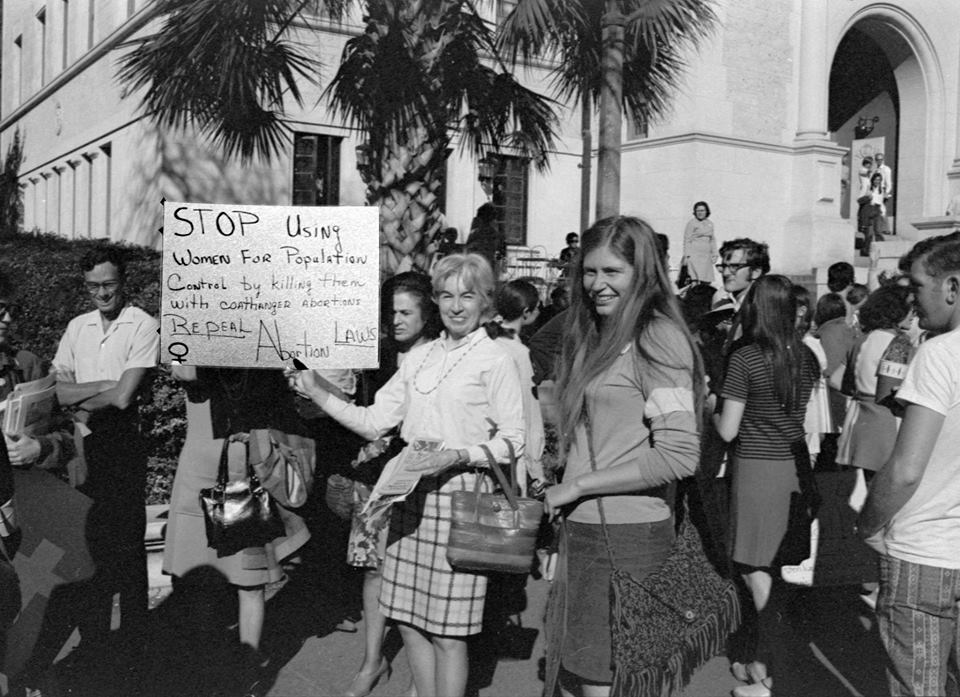

Before moving to Missoula, Judy Smith was active in the feminist movement in Texas. She poses here with her mother at the first Texas statewide women’s reproductive rights conference at the University of Texas Student Union in Austin in 1971. Photo by Alan Pogue, courtesy The Rag, http://www.theragblog.com/alice-embree-and-phil-primm-remembering-judy-smith/

Judy Smith was a fixture in Montana’s feminist community from her arrival in the state in 1973 until her death in 2013. Her four decades of activism in Missoula encapsulated the “second wave” of American feminism.

Like many of her contemporaries, Smith followed the “classic” trajectory from the student protest, civil rights, and anti-Vietnam War movements of the 1960s into the women’s movement of the 1970s. While pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Texas, Smith joined a reproductive rights group. Because abortion was banned in the United States, she sometimes ferried desperate women over the border to Mexico to procure abortions. Knowing her actions were illegal, Smith consulted a local lawyer, Sarah Weddington. These informal conversations sparked the idea of challenging Texas’s anti-abortion statutes, culminating in the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade. From this success, Smith learned that “any action that you take . . . can build into something.”

Smith brought her conviction that grassroots activism was the key to social change with her to Missoula. As she later characterized her approach, she simply looked around her adopted hometown and demanded: “What do women need here? Let’s get it going. Get it done.”

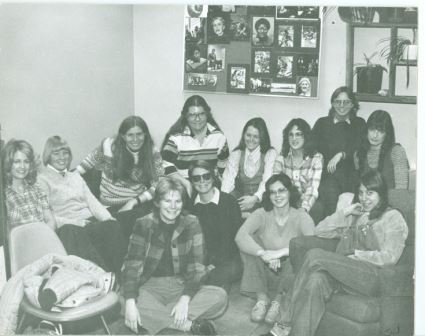

Members of the Women’s Resource Council, pictured here, were the nucleus of feminist activism in Missoula in the 1970s and 1980s. Among other services, the WRC provided free classes for women on everything from auto mechanics to assertiveness training. Diane Sands Papers, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 19 (Women’s Resource Center Photographs, 1975-1983), University of Montana Archives

Smith’s first step was to revitalize the University of Montana’s struggling feminist organization. In addition to finding new space and obtaining increased funding for the Women’s Resource Center (WRC), Smith expanded the group’s activities to include weekly films, brown bag discussions, and hands-on workshops. The WRC’s newsletter circulated throughout Montana, fostering a statewide feminist network.

Smith forged links between local activists and the national movement. With UM graduate and WRC member Diane Sands, she initiated an annual women’s conference, bringing nationally renowned feminists to Missoula and encouraging Montanans to imagine a “feminist future.”

Smith educated and empowered generations of women. Using her academic credentials, she attained faculty affiliate status and taught women’s studies courses—off the books and open to all—for over a decade, introducing hundreds of college students and community members to “Feminism 101.” Smith also shared her knowledge of grassroots organizing and her grant-writing skills with future activists.

For Smith, who identified herself as a radical feminist, grassroots activism was always “steeped in feminist theory.” “Feminism to me isn’t just about women, it’s also about oppression,” she maintained. “Women are a class and they’re oppressed in certain ways and power is the issue. It’s not enough just to provide services[;] even though that’s important, it doesn’t ask the fundamental question of why is the situation the way it is, and what can you do about that situation . . . It’s a systems analysis as well as a service analysis.”

Bringing together university students and community activists, Smith established new feminist organizations, most notably Blue Mountain Women’s Clinic, which provided a full range of health care, including abortion, and Women’s Place, a rape crisis center. Missoula’s feminist organizations mirrored the national women’s movement. As Smith acknowledged, “feminism . . . was always a national movement,” even though much of the work occurred locally.

Usually spontaneously and almost simultaneously, women’s groups addressing similar issues sprang up around the country in the 1970s and 1980s. They also developed similar group dynamics, struggling to reconcile their ideological commitment to equality with real power differences.

Smith’s activism spanned more than forty years. Pictured here speaking in the Capitol rotunda on January 22, 2013, at an event marking the 40th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision on Roe v. Wade, Smith holds a 1970 photograph of herself engaged in reproductive rights counseling, taken by Alan Pogue, her coworker at the Texas underground newspaper The Rag. Photo by Eliza Wiley, Helena Independent Record

An imposing figure who stood six feet tall, Smith inspired many but intimidated others. Her forceful personality ran counter to the prevailing philosophy of feminist collectivism. Smith “never belonged to a group she did not control,” comments Sands. But unlike some second-wave feminists, she avoided “trashing” her colleagues. When conflict escalated, she simply moved on. She had “the courage to be innovative,” reflects colleague Terry Kendrick, “to pick herself up the next day and get started on something else.”

Many second-wave feminist organizations were fraught with conflict. As early as 1978, the WRC membership registered “concern and confusion” about “power holders” whose “knowledge and skills” granted them unofficial authority and decision-making power in a group that prized “consensus” and “dialogue.” By the mid-1980s, Missoula’s feminists were bitterly divided.

Smith also confronted growing opposition from campus officials worried that the WRC’s radio program on the UM station openly discussed both lesbianism and witchcraft. “She needed to find another institutional base,” explains Sands. That base was Women’s Opportunity and Resource Development (WORD), which Smith created by writing a grant for a program that used welfare funding to provide higher education and vocational training to low-income women.

Under Smith’s guidance, WORD became an incubator for new organizations. One of WORD’s earliest projects, providing small grants for local businesses, later became the Montana Community Development Organization. HomeWORD, an affordable and sustainable housing program, also had its origins at WORD.

Once these projects were launched, Smith turned her attention to public policy, dedicating the last decade of her life to promoting a living wage, affordable housing, and sustainable development through her work with Montana Women Vote, a voter-education group.

Smith was a visionary, with “an uncanny ability . . . to see what the next wave of the [women’s] movement was going to be,” marvels Kendrick. Smith herself attributed progress to collaboration, insisting, “the women’s movement did this work.”

Convinced that only collective action could create meaningful change, Smith encouraged young women to get involved. Only if successive generations of women engaged in political activism could feminism be what Smith called “a living tradition.”

Smith lived the women’s liberation mantra, “the personal is political.” Despite occasional differences with others, she also believed another second-wave maxim, “sisterhood is powerful.” Judy Smith truly embodied second-wave feminism. AJ

Sources

“Alice Embree and Phil Prim: Remembering Judy Smith,” January 15, 2014. http://www.theragblog.com/alice-embree-and-phil-primm-remembering-judy-smith/

Cohen, Betsy. “Women’s Rights, Peace Activist Judy Smith Remembered for Her Legacy.” Missoulian, November 11, 2013, http://missoulian.com/news/local/women-s-rights-peace-activist-judy-smith-remembered-for-her/article_fd1f442a-4a90-11e3-b201-001a4bcf887a.html

Judy Smith obituary. Missoulian, November 10, 2013. http://missoulian.com/news/local/obituaries/judith-hart-smith/article_44ef3216-4a27-11e3-9a2f-0019bb2963f4.html.

Kendrick, Terry. Interview by author, January 2, 2014.

Montana Feminist History Project, Archives and Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula.

Sands, Diane. Interview by author, December 12, 2013.

Smith, Judy. Interview by Dawn Walsh, April 23, 2001. OH 378-48, Archives & Special Collections Department, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana (hereafter UM).

—. Interview by Erin Cunniff, March 7, 2002. OH 378-3, UM.

—. Interview by Jack Rowan, April 30, 2006. OH 400-3, UM.

Smith, Linda. Interview by Erin Cunniff and Darla Torres, March 19, 2002. OH 378-4, UM.

“Think BIG & ACT: Missoula Feminists Judy Smith & Honorable Jim Wheelis.” Blue Mountain Clinic History Project, interview conducted by Lynsey Bourke, January 28, 2013, posted November 11, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3aEK4U0_nc.

Weddington, Sarah. A Question of Choice: By the Lawyer Who Won Roe v. Wade. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1992; rev. ed. Feminist Press, 2013.

Below is a link to Dawn Walsh’s interview with Judy Smith in 2001: